You are in a maze of twisty little passages, all alike

Not too long ago I was in a bar with a friend, talking about if and how video games can function as art. Like most grandiose barroom conversations, we glossed over a few small details: for example, the whole question of What Is Art? And while maybe someday I’ll take a tilt at that windmill, right now I just don’t have the energy; my daughter has been sick, and it’s the end of a long week.

In sober retrospect though, that discussion has got me wondering about a more immediate and answerable issue: why video games don’t work as art for me. In particular, I’m thinking about the flavor of video game (I use the term broadly) that seems to aspire most specifically to the status of art, both through its relatively abstract structure and its appeal to the conventions of narrative: the text adventure, aka “interactive fiction.”

For those not familiar with the genre, this overview is from the website of Adam Cadre, among the most respected contemporary IF authors:

To most people who’ve heard of it, the entry for “interactive fiction” in their mental dictionaries goes something like this: “Interactive fiction, noun. A fancy name for text adventures, a type of computer game popular in the early 1980s despite having no graphics. Usually involved wandering around in caves solving complicated puzzles, and became completely obsolete around the time Reagan left office, as graphics became less crappy.”

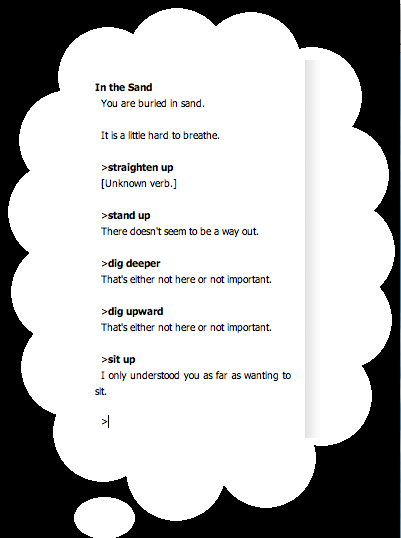

The problem with this definition is that the medium of interactive fiction is no more a relic of the 1980s than the novel is a relic of the 17th century. If you’ve never encountered it before, it works like this: you start up the program and it prints out the first paragraph or two (or, um, nine) of a story. Then suddenly there’s an angle bracket and a blinking cursor: it’s your turn to type. For in interactive fiction (IF for short), you don’t just read the story — you get to shape it. Usually you’ll be typing instructions for one of the characters to follow — and unlike in a “choose your own adventure” story, you’re not just picking from a menu, but can type anything you can think of.

It seems to me that, in other words, “interactive fiction” aspires to an organic storytelling experience, which (at least partially) effaces the distinction between listener and teller. In practice though, the effect is often the exact opposite of a natural conversational flow — what I privately think of as synonym hell, trying to find the exact combination of words that the game expects:

Even aside from this essentially technical limitation though, I think there’s a deeper issue which gets in the way of my enjoyment of IF. Way back when, I went through a (very brief) phase of reading “choose your own adventure” books. (In particular, I remember one memorably titled You Are a Shark!) The problem with these books was not, as Adam Cadre suggests, the limited and/or stupid choices available to me as a reader at each juncture of the plot. Instead, it was the fact of having to make those choices at all.

For me, maybe the greatest pleasure and promise of reading is the opportunity to spend a few hours or days hanging out in someone else’s head: the chance to look at the world as it might seem to someone else, with different priorities, impulses, and insights. Reading great books is an opportunity to try on different modes of being. But in order for that magic to work, the characters in a story need to come alive. On an intuitive level, we need to be able to project our own selfhood into theirs.

So the issue with “interactive fiction” — like “choose your own adventure” — is that it deprives the characters in a story of their own personhood. How can I believe that a character is “real” if they can’t even make their own decisions — but instead rely on me to choose door X vs. door Y, stay and fight or run away? The net result is to hollow out the characters, making them nothing more than puppets. So rather than creating a bridge between myself and anther kind of living, “interactive fiction” winds up feeling to me like a kind of sad masquerade in which I remain myself, but less so — since the richness of real life is narrowed down to a constrained and essentially foreign set of choices imposed by the author, with no basis in my own selfhood or that of anyone else.