Two weeks ago I was contacted by a librarian at the Mentor Public Library (near Celeveland, Ohio). A book group at the library was reading KOH, and they were interested in sending a few questions my way. At the time, I was feeling a bit adrift in terms of my current project so I welcomed the excuse for procrastination.

Answering the group’s questions was a fun exercise, so I thought I’d post them here. (For those in the Cleveland area, the group has a website.)

1. Do you have any plans for a prequel or a sequel, and if not do you have thoughts on what happened to your characters Peter and Cheri.

At the moment I’m not planning a sequel: my current project is a historical novel set in the 17th century Ottoman Empire – although I don’t absolutely rule out the possibility of a follow-up to KOH someday.

As for what happened to Peter and Cheri-Anne, the end of the novel is left intentionally ambiguous. In a sense, KOH is a cautionary tale about the dangers of clinging to a particular story. By the time Peter returns to New York he has spent the better part of his life obsessing over the past, at the expense of the present; at the conclusion of the book he (literally) steps away from that well-trodden, obsessive narrative into the unknown future – the part of the map inscribed with the warning, “here be dragons” which may, or may not, coincide with his own death.

That said, I have a feeling Cheri-Anne survived and found a place to call home somewhere.

2. Did you have any specific authors that you drew upon for the sci-fi/ time travel elements?

I’m not aware of particular authors who influenced the sci-fi elements of the book, but the novel as a whole is deeply indebted to Mark Helprin, specifically A Winter’s Tale,, which is set in a similar version of New York City.

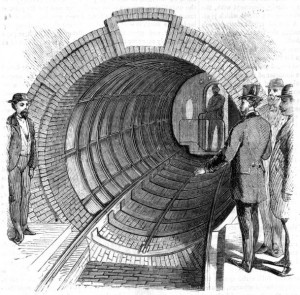

3. Any reason for the use of the subway tunnels and time travel…tunneling through time and tunneling through the earth?

My decision to use the NY subway tunnels in the book was the result of some fairly convoluted personal history – so you’ll have to bear with me on this one.

Several years ago I visited the “Seattle underground,” a network of semi-abandoned tunnels beneath that city. There’s an interesting story behind these passageways: Seattle was originally a logging port where cut timber was loaded onto ships. At the time, most of the town was built on a tidal flat, and the streets were paved with sawdust. As you can imagine, this led to some problems. For one thing, because the town was at sea level, there were serious plumbing issues: if someone flushed their toilet at high tide, it resulted in a geyser of sewage. For another, the town was prone to flooding – and when it did flood, the sawdust streets turned into a morass that could swallow up incautious dogs and small children.

Then 1889 the Great Seattle Fire destroyed about 25 blocks including most of the old downtown. When the city leaders started to rebuild, they decided to raise the street level by ten feet, the second floor of the old buildings becoming the new ground level.

This had the side-effect of creating a kind of underground city. The old streets became tunnels that linked the buried portion of the buildings. These tunnels became the domain of smugglers and runaways and pirates, a kind of secret city beneath Seattle. Over the years, they fell into disrepair and were finally forgotten for decades.

When I visited the tunnels, they struck me as a metaphor for America’s relationship with its past: how we tend to smooth over the messy parts of history, so that progress looks like a straight line rather than a series of false starts, detours and accidents. Although Seattle itself didn’t make it into the book, the echoes of those tunnels survived.

Specifically, one of the themes that interested me was the intersection between our idiosyncratic personal histories and our relatively homogenous sense of shared history. Both the subway tunnels (the underside of visible existence) and time travel (a rupture in the historical process) felt to me like ways of playing with that relationship.

4. There seemed to be a lot about memory, madness and identity in the story. (Cheri would be considered mad for her memories of her past life, Peter keeps switching his identity with counterfeit paperwork, Peter continually recalls his memories of Cheri, Tesla feels his memory is ironclad, etc.) How did you choose to put these themes into the story and connect them with the “relative state formulation” discussed on page 250?

The process of writing a novel, for me, is more like having a conversation (with myself and the reader) about certain ideas or themes, rather than putting forth a well-defined thesis.

In this book, the themes of memory, madness, and identity are, for me, all connected with the sense of history I mentioned above. Our memories are the building blocks of our identity: our sense of the past, and our relationship with that past, largely defines our selves.

But what happens when our private experience of selfhood comes into conflict with history writ large? Normally our identities are a kind of negotiated compromise between what other people think of us, and how we see ourselves. The discrepancies between the two can be both a source of strength (the private hopes we nurture) and great pain (for example, in the case of invisible minorities). In KOH, Peter’s false identities and Cheri-Anne’s struggle with her past are different kinds of rupture between who we know ourselves to be, and who the world thinks we are.

I’m not sure if I see a (direct) connection between these themes and the brief discussion of “relative state formation,” which relates more to the paradoxes of time travel and causality.

5. Names often have significance and can be symbolic. Do you think the names you chose for the characters and for the name on the door, “CROATOAN,” were specifically chosen, and if so why those?

I chose the name “Cheri-Anne Toledo” because it struck me as at once elaborately royal and otherworldly. The “cheri” (precious, or darling, in French) seemed to work as a reference to the Latoledan family ancestry and a veiled suggestion of the cosseted, over-protected life that she lead before arriving in New York.

The names “Peter Force” and “CROTOAN” are much less the product of a writerly plan: I once met a Peter Force, and it had a ring that I liked. My use of CROTOAN is, as they say, “over-determined†in that it comes from at least three different sources.

The first is a fantastic short story (of the same name) by Harlan Ellison, in which the narrator descends into New York City’s sewers where he finds a tribe of crocodile-riding fetuses, and this word crudely lettered on a wall; second, it’s the title of my favorite album by the greatest pop star the world never knew; and third, the history of the lost Roanoke Colony itself (which is briefly described at the end of the book). Between those things, I couldn’t resist; my only regret is that I couldn’t work in the crocodiles too.